Our Purpose

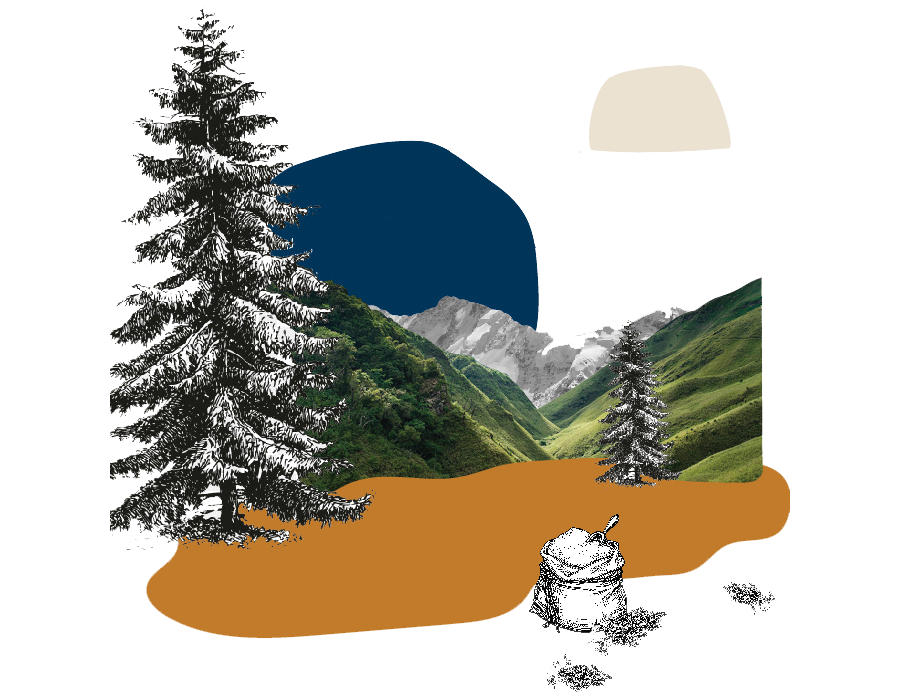

The ethereally high altitudes and arduous terrain of the Himalaya instil a sense of awe — an otherworldliness that’s majestic yet vulnerable. Its magnificence has, in equal parts, challenged intrepid explorers, and sheltered its own people and cultures, cultivating a way of life that is unique, warm, and unparalleled in its harmony with the natural world.

The Himalayan Way of Life is the ancient wisdom of nurturing and sustaining the balance between our natural world and human needs; a seamless approach to co-creating in partnership with nature.

The earliest texts about the creation of our world articulate the primordial elements of earth, water, fire, air and ether as the building blocks of our planet. The Himalayan Way of Life is about understanding, exploring and reenergising their interconnectedness with human health and wellbeing.

The resilience of the Himalayan ecosystem is a source of great hope for humankind. Preserving the Himalayan Way of Life can help make the planet at large more liveable in the face of the mounting global climate crisis.

At Himalayan Essence, we are passionate about conserving and restoring the Himalayan ecosystem through nature-based solutions. By collaborating with small-holding farmers in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR), we work towards amalgamating the ancient wisdom of traditional regenerative agricultural practices with modern technology, tools and markets.

Himalayan Way of Life

We at Himalayan Essence are inspired by these five Sustainable Development Goals

Zero Hunger

Good Health & well-being

Responsible Consumption & Production

Climate Action

Life on Land

-

![]()

NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

The answers to the conundrums of restoring and protecting our natural world lie in nature too. Nature-based solutions offer the unique path of simultaneously pursuing planetary and human well-being. From expanding nature reserves to restoring ecosystems rich in species such as the Himalaya, nature-based solutions can boost biodiversity, reabsorb carbon, and address the need for local livelihood, and nutrition for consumers.

NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

The answers to the conundrums of restoring and protecting our natural world lie in nature too. Nature-based solutions offer the unique path of simultaneously pursuing planetary and human well-being. From expanding nature reserves to restoring ecosystems rich in species such as the Himalaya, nature-based solutions can boost biodiversity, reabsorb carbon, and address the need for local livelihood, and nutrition for consumers.

OUR WORKPLACES

Farmers in the Himalaya place utmost importance on the “culture” in agriculture. Little wonder then, no matter where you go in the Himalaya, you are sure to find a festival that celebrates the deep bond between nature and people.

-

![]()

Jammu

In Jammu, Lohri is celebrated in January to mark the beginning of harvest season. A special dance called the ‘Chajja’ dance is held on the occasion.

-

![]() Pann picture source: Shehjar.com

Pann picture source: Shehjar.comKashmir

In Kashmir, the Hindu Pandit community celebrates the festival of Pann on the day of Ganesh Chaturthi in September. “Pann” literally means cotton/ thread. The festival is celebrated to honour the agricultural goddesses, Vibha and Garbha.

-

![]()

Ladakh

The Brokpa Dard community of Kargil in Ladakh celebrates Bonona or Chhopo Srub-La to offer gratitude to their Gods for good harvest and prosperity for the tribe. The festival is celebrated every three years with great fanfare in early October.

-

![]() Picture source: Testbook.com

Picture source: Testbook.comHimachal Pradesh

Declared one of the state fairs of Himachal Pradesh, Minjar is held on the second Sunday of the Shravana month (July/August) in the Chamba district. Men and women alike wear silk tassels symbolising shoots of paddy and maize, the new crop. Idols of deities are brought out of temples amidst cheer and celebrations.

-

![]() Picture source: Jaimitra Singh Bisht

Picture source: Jaimitra Singh BishtUttarakhand

Harela is celebrated in the Hindu Lunar month of Shravan (July/August) commemorating the start of monsoon and harvest season in the Kumaon region. Seeds of maize, sesame, black gram, mustard, and oats are sown in donas (leaf bowls) or ringalare (hill bamboo baskets) nine days before the festival, harvested on Harela, and distributed in the community for prosperity in the year ahead.

-

![]()

Sikkim

Losoong is the Sikkimese new year, also celebrated as the Farmer’s New Year. While it is traditionally a festival of the Bhutia tribe, the Lepchas also celebrate it, and call it Namsoong. Every December as part of the Losoong celebration, Buddhist monks perform plays that symbolically dispel evil in the year gone by and welcome good omens in the year to come. -

![]()

Arunachal Pradesh

The Apatani tribe of Arunachal Pradesh are known for their unique paddy cultivation practices. They perform rituals during the month of Dree to ward off insects, pests, disease and famine. In modern times the ritual has transformed into a festival and takes place every July. Festivities are marked with Pri-dances, Daminda and other folk dances with gaiety. -

![]()

Nagaland

The Konyak tribe of Nagaland celebrate the spring harvest festival of Aoling in the first week of April. On Lingnyu Nyih - the fourth day of the week-long celebration, people dress up in festive clothing and come together to dance, sing and celebrate the bounty of spring and seek blessings for the Konyak new year. -

![]()

Manipur

Chavang Kut, popularly known as the Kut festival is celebrated by the tribes of Kuki-Chin-Mizo groups of Manipur. Roughly translated, ‘Chavang’ means ‘autumn’ and Kut means ‘harvest’. The festival is celebrated every year in November with folk dances and traditional songs. It also marks the end of the harvest season. -

![]()

Mizoram

Chaphar Kut is celebrated by the Mizo people to mark the onset of spring in February/ March. On the festival, the people offer gratitude to the almighty for protecting them during the traditional Jhum cultivation. Men and women perform the traditional Cheraw dance with bamboos. -

![]()

Meghalaya

The Khasis of Meghlaya celebrate the festival of Ka Shad Suk Mynsiem – literally translating to “Dance with a Peaceful Heart” – every year in April. It is the Khasi way of expressing gratitude for a bountiful harvest and is characterized by various symbolic rituals and dances. The female dancers are clad in the best silks, and adorned with gold, coral, and silver accessories. Shad Suk Mynsiem is an agrarian festival and commemorates the advent of spring as a season of rebirth and fertility.

OUR WORKPLACES

Farmers in the Himalaya place utmost importance on the “culture” in agriculture. Little wonder then, no matter where you go in the Himalaya, you are sure to find a festival that celebrates the deep bond between nature and people.

-

![]()

Jammu

In Jammu, Lohri is celebrated in January to mark the beginning of harvest season. A special dance called the ‘Chajja’ dance is held on the occasion.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Kashmir

Pann picture source: Shehjar.comIn Kashmir, the Hindu Pandit community celebrates the festival of Pann on the day of Ganesh Chaturthi in September. “Pann” literally means cotton/ thread. The festival is celebrated to honour the agricultural goddesses, Vibha and Garbha.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Ladakh

The Brokpa Dard community of Kargil in Ladakh celebrates Bonona or Chhopo Srub-La to offer gratitude to their Gods for good harvest and prosperity for the tribe. The festival is celebrated every three years with great fanfare in early October.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Himachal Pradesh

Picture source: Testbook.comDeclared one of the state fairs of Himachal Pradesh, Minjar is held on the second Sunday of the Shravana month (July/August) in the Chamba district. Men and women alike wear silk tassels symbolising shoots of paddy and maize, the new crop. Idols of deities are brought out of temples amidst cheer and celebrations.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Uttarakhand

Picture source: Jaimitra Singh BishtHarela is celebrated in the Hindu Lunar month of Shravan (July/August) commemorating the start of monsoon and harvest season in the Kumaon region. Seeds of maize, sesame, black gram, mustard, and oats are sown in donas (leaf bowls) or ringalare (hill bamboo baskets) nine days before the festival, harvested on Harela, and distributed in the community for prosperity in the year ahead.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Sikkim

Losoong is the Sikkimese new year, also celebrated as the Farmer’s New Year. While it is traditionally a festival of the Bhutia tribe, the Lepchas also celebrate it, and call it Namsoong. Every December as part of the Losoong celebration, Buddhist monks perform plays that symbolically dispel evil in the year gone by and welcome good omens in the year to come.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Arunachal Pradesh

The Apatani tribe of Arunachal Pradesh are known for their unique paddy cultivation practices. They perform rituals during the month of Dree to ward off insects, pests, disease and famine. In modern times the ritual has transformed into a festival and takes place every July. Festivities are marked with Pri-dances, Daminda and other folk dances with gaiety.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Nagaland

The Konyak tribe of Nagaland celebrate the spring harvest festival of Aoling in the first week of April. On Lingnyu Nyih - the fourth day of the week-long celebration, people dress up in festive clothing and come together to dance, sing and celebrate the bounty of spring and seek blessings for the Konyak new year.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Manipur

Chavang Kut, popularly known as the Kut festival is celebrated by the tribes of Kuki-Chin-Mizo groups of Manipur. Roughly translated, ‘Chavang’ means ‘autumn’ and Kut means ‘harvest’. The festival is celebrated every year in November with folk dances and traditional songs. It also marks the end of the harvest season.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Mizoram

Chaphar Kut is celebrated by the Mizo people to mark the onset of spring in February/ March. On the festival, the people offer gratitude to the almighty for protecting them during the traditional Jhum cultivation. Men and women perform the traditional Cheraw dance with bamboos.

Explore the Himalaya -

![]()

Meghalaya

The Khasis of Meghlaya celebrate the festival of Ka Shad Suk Mynsiem – literally translating to “Dance with a Peaceful Heart” – every year in April. It is the Khasi way of expressing gratitude for a bountiful harvest and is characterized by various symbolic rituals and dances. The female dancers are clad in the best silks, and adorned with gold, coral, and silver accessories. Shad Suk Mynsiem is an agrarian festival and commemorates the advent of spring as a season of rebirth and fertility.

Explore the Himalaya